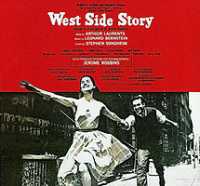

West Side Story is an American musical with a script by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and choreographed by Jerome Robbins. It is an adaptation of William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet.

Set in New York City in the mid-1950s, the musical explores the rivalry between the Jets and the Sharks, two teenage street gangs of different ethnic backgrounds. The members of the Sharks from Puerto Rico are taunted by the Jets, a white working-class group.[1] The young protagonist, Tony, one of the Jets, falls in love with Maria, the sister of Bernardo, the leader of the Sharks. The dark theme, sophisticated music, extended dance scenes, and focus on social problems marked a turning point in American musical theatre. Bernstein's score for the musical has become extremely popular; it includes "Something's Coming", "Maria", "America", "Somewhere", "Tonight", "Jet Song", "I Feel Pretty", "A Boy Like That", "One Hand, One Heart", "Gee, Officer Krupke" and "Cool".

The original 1957 Broadway production, directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins and produced by Robert E. Griffith and Harold Prince, marked Stephen Sondheim's Broadway debut. It ran for 732 performances (a successful run for the time), before going on tour. The production received a Tony Award nomination for Best Musical in 1957, but the award went to Meredith Willson's The Music Man. It won a 1957 Tony Award for Robbins' choreography. The show had an even longer-running London production, a number of revivals and international productions. The play spawned an innovative 1961 musical film of the same name, directed by Robert Wise and Robbins, starring Natalie Wood, Richard Beymer, Rita Moreno, George Chakiris and Russ Tamblyn. The film won ten Academy Awards out of eleven nominations. The stage musical is produced frequently by schools, regional theatres, and occasionally by opera companies.

Genesis of the concept

In 1949, Jerome Robbins approached Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Laurents about collaborating on a contemporary musical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. He proposed that the plot focus on the conflict between an Irish American Roman Catholic family and a Jewish family living on the Lower East Side of Manhattan,[2] during the Easter–Passover season. The girl has survived the Holocaust and emigrated from Israel; the conflict was to be centered around anti-Semitism of the Catholic "Jets" towards the Jewish "Emeralds" (a name that made its way into the script as a reference).[3] Eager to write his first musical, Laurents immediately agreed. Bernstein wanted to present the material in operatic form, but Robbins and Laurents resisted the suggestion. They described the project as "lyric theatre," and Laurents wrote a first draft he called East Side Story. Only after he completed it did the group realize it was little more than a musicalization of themes that had already been covered in plays like Abie's Irish Rose. When he opted to drop out, the three men went their separate ways, and the piece was shelved for almost five years.[4][5]

In 1955, theatrical producer Martin Gabel was working on a stage adaptation of the James M. Cain novel Serenade, about an opera singer who comes to the realization he is homosexual, and he invited Laurents to write the book. Laurents accepted and suggested Bernstein and Robbins join the creative team. Robbins felt if the three were going to join forces, they should return to East Side Story, and Bernstein agreed. Laurents, however, was committed to Gabel, who introduced him to the young composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim. Sondheim auditioned by playing the score for Saturday Night, his musical that was scheduled to open in the fall. Laurents liked the lyrics but wasn't impressed with the music. Sondheim didn't care for Laurents' opinion. Serenade ultimately was shelved.[6]

Laurents was soon hired to write the screenplay for a remake of the 1934 Greta Garbo film The Painted Veil for Ava Gardner. While in Hollywood, he contacted Bernstein, who was in town conducting at the Hollywood Bowl. The two met at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and the conversation turned to juvenile delinquent gangs, a fairly recent social phenomenon that had received major coverage on the front pages of the morning newspapers due to a Chicano turf war. Bernstein suggested they rework East Side Story and set it in Los Angeles, but Laurents felt he was more familiar with Puerto Ricans and Harlem than he was with Mexican Americans and Olvera Street. The two contacted Robbins, who was enthusiastic about a musical with a Latin beat. He arrived in Hollywood to choreograph the dance sequences for The King and I, and he and Laurents began developing the musical while working on their respective projects, keeping in touch with Bernstein, who had returned to New York. When the producer of The Painted Veil replaced Gardner with Eleanor Parker and asked Laurents to revise his script with her in mind, he backed out of the film, freeing him to devote all his time to the stage musical

In New York, Laurents went to the opening night party for a new play by Ugo Betti, and there he met Sondheim, who had heard that East Side Story, now retitled West Side Story, was back on track. Bernstein had decided he needed to concentrate solely on the music, and he and Robbins had invited Betty Comden and Adolph Green to write the lyrics, but the team opted to work on Peter Pan instead. Laurents asked Sondheim if he would be interested in tackling the task. Initially he resisted, because he was determined to write the full score for his next project (Saturday Night had been aborted), but Oscar Hammerstein convinced him that he would benefit from the experience, and he accepted.[8] Meanwhile, Laurents had written a new draft of the book changing the characters' backgrounds: Anton, once an Irish American, was now of Polish and Irish descent, and the formerly Jewish Maria had become a Puerto Rican.[9]

The original book Laurents wrote closely adhered to Romeo and Juliet, but the characters based on Rosaline and the parents of the doomed lovers were eliminated early on. Later the scenes related to Juliet's faking her death and committing suicide also were deleted. Language posed a problem; four-letter curse words were uncommon in the theatre at the time, and slang expressions were avoided for fear they would be dated by the time the production opened. Laurents ultimately invented what sounded like real street talk but actually wasn't: "cut the frabba-jabba", for example.[10] Sondheim converted long passages of dialogue, and sometimes just a simple phrase like "A boy like that would kill your brother," into lyrics. With the help of Oscar Hammerstein, Laurents convinced Bernstein and Sondheim to move "One Hand, One Heart", which he considered too pristine for the balcony scene, to the scene set in the bridal shop, and as a result "Tonight" was written to replace it. Laurents felt that the building tension needed to be alleviated in order to increase the impact of the play's tragic outcome, so comic relief in the form of Officer Krupke was added to the second act. He was outvoted on other issues: he felt the lyrics to "América" and "I Feel Pretty" were too witty for the characters singing them, but they stayed in the score and proved to be audience favorites. Another song, "Kid Stuff", was added and quickly removed during the Washington, D.C. tryout when Laurents convinced the others it was helping tip the balance of the show into typical musical comedy.[11]

Bernstein composed West Side Story and Candide concurrently, which led to some switches of material between the two works.[12] Tony and Maria's duet, "One Hand, One Heart," was originally intended for Cunegonde in Candide. The music of "Gee, Officer Krupke" was pulled from the Venice scene in Candide.[13] Laurents explained the style that the creative team finally decided on: "Just as Tony and Maria, our Romeo and Juliet, set themselves apart from the other kids by their love, so we have tried to set them even further apart by their language, their songs, their movement. Wherever possible in the show, we have tried to heighten emotion or to articulate inarticulate adolescence through music, song or dance."[14]

The show was nearly complete in the fall of 1956, but almost everyone on the creative team needed to fulfill other commitments first. Robbins was involved with Bells Are Ringing, then Bernstein with Candide, and in January 1957 A Clearing in the Woods, Laurents' latest play, opened and quickly closed.[15] When a backers' audition failed to raise any money for West Side Story late in the spring of 1957, only two months before the show was to begin rehearsals, producer Cheryl Crawford pulled out of the project.[16] Every other producer had already turned down the show, deeming it too dark and depressing. Bernstein was despondent, but Sondheim convinced his friend Hal Prince, who was in Boston overseeing the out-of-town tryout of the new George Abbott musical New Girl in Town, to read the script. He liked it but decided to ask Abbott, his longtime mentor, for his opinion, and Abbott advised him to turn it down. Prince, aware that Abbott was the primary reason New Girl was in trouble, decided to ignore him, and he and his producing partner Robert Griffith flew to New York to hear the score.[17] In his memoirs, Prince recalled, "Sondheim and Bernstein sat at the piano playing through the music, and soon I was singing along with them."[1