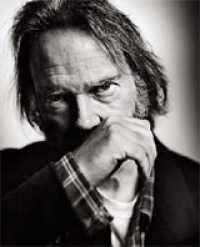

IN the course of his thirty-year career as a recording artist, Neil Young has experienced as many extreme low points of critical and commercial success as he has high, but without a doubt, he is one of the most important rock composers and performers North America can claim. His signature raw nasal tone, shrill guitar playing, highly personal lyric-writing, and hippie-cowboy loner stance have helped shape rock and roll as it has advanced from adolescence into maturity. Through his experimentation with every genre, from folk to heavy metal to rockabilly to techno, Young has created a sound and feel uniquely his own.

Born the son of Edna "Rassy" Young, a former quiz show panelist on Canadian Television, and Scott Young, a sportswriter for the Toronto Sun, Young's first musical inklings were encouraged when his father gave him a ukulele for Christmas in 1958. His parents split up not too long after that, and in 1960, Young moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, with his mother. A rather apathetic student, he was far more interested in playing the banjo and guitar than turning his mind to his studies, and he eventually dropped out of high school to concentrate his attention on the band he had formed, Neil Young & the Squires.

Mrs. Young supported her son's musical endeavors, and through her aggressive booking, helped the Squires gain a fair amount of regional notoriety. Drawing influence from Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Ventures, and the Shadows, the band evolved from an instrumental group to a folk-rock band, and began performing in clubs around the area between 1963 and 1965.

After the Squires disbanded in the summer of 1965, Young recorded some demos for Elektra Records, but failed to secure a contract. He spent the rest of the year playing the Toronto coffeehouse circuit, both as a solo artist and with the Mynah Birds, a group fronted by future soul-music star and "Super Freak," Rick James. On the circuit, Young met a number of folk artists, including Joni Mitchell, guitarist Richie Furay, and Stephen Stills, who was then playing with his own folk band, the Company.

When the Mynah Birds disbanded after recording one album, Young and Mynah Birds bassist Bruce Palmer moved to the promised land of L.A., where they hooked up with Stills, Furay, and drummer Dewey Martin to form the seminal folk-rock band the Buffalo Springfield. Stills' counterculture anthem "For What It's Worth" earned the band nationwide fame, but it was Young who drew the most attention for his idiosyncratic style and high-energy guitar playing. In their two-year existence, the band recorded three successful albums and a retrospective (Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield Again, Last Time Around, and The Best of the Buffalo Springfield) for Atco before splintering in 1968.

Following the demise of the band, Young signed a solo deal with Reprise Records, and released a poorly received eponymous debut in January of 1969. His second solo effort, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, recorded in his own studio setup at his Topanga, California, home with his new backing band Crazy Horse (the band's original lineup included lead guitarist Danny Whitten, bassist Billy Talbot, drummer Ralph Molina, and pianist-producer-arranger Jack Nitzsche), became a major hit and went platinum on the strength of songs like "Cinnamon Girl," "Cowgirl in the Sand," and "Down by the River." With the understanding that he could come and go as he pleased, Young elected to join David Crosby, Steven Stills, and Graham Nash's supergroup in the summer of 1969, just in time to appear at the historic Woodstock Festival.

Young eventually recorded three albums as part of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young: 1970's Deja Vu, 1971's live 4-Way Street, and 1988's American Dream. Hailed as "quite possibly the most important new poet since Bob Dylan," Young's notable songwriting contributions to the collective included "Helpless," "Country Girl," and "Ohio." In Young's estimation, the latter song, written in response to the tragic shooting deaths of four students at an anti-Vietnam rally at Kent State University in May of 1970, was his best C.S.N. & Y. cut.

Young's solo career was simultaneously soaring, as 1970's After the Gold Rush and 1972's Harvest both became bestsellers and were immediately recognized as classics. Harvest, which was recorded in Nashville with the Stray Gators and crossover pop-rock stars Linda Ronstadt and James Taylor, was the biggest-selling album of 1972, and the cut "Heart of Gold" remains the most successful single of Young's career. Between 1972 and 1977, Young released a sequence of six introspective albums of impressive scope (Journey Through the Past, Time Fades Away, On the Beach, Tonight's the Night, Zuma, and American Stars 'n Bars); haunting loss permeated many of his songs during this prolific period, most obviously because of the devastating drug-related deaths of Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten and roadie Bruce Berry.

In 1977, the release of a double-album retrospective, Decade, attested to Young's importance in rock history. He closed the seventies on a peak with the lighthearted, philosophical Comes a Time, and a half-acoustic, half-electric album, Rust Never Sleeps, so titled at the suggestion of the members of the new-wave group Devo, who thought the Rustoleum slogan, "Rust never sleeps," made a catchy-sounding title. A rollicking live album, Live Rust, and the generally poorly received concert film Rust Never Sleeps resulted from the 1978 tour for the album.

Depending on one's perspective, Young either lost focus in the early- to mid-eighties or deserves credit as an ambitious explorer. Jumping wildly between genres, he opened the decade with the country-tinged Hawks & Doves, moved into Kraftwerk-like electronic sounds with Trans and retro-rockabilly on Everybody's Rockin', but still tore it up with Crazy Horse on Re-act-or and on 1987's Life. The next year, Young headed in a horn-driven, soulful direction with a new band, the Bluenotes, on This Note's for You. The title track won MTV's Video of the Year award, despite the fact that the clip was banned by the network — lampooning the commercial state of rock, the video shows a Michael Jackson look-alike's hair catching fire and being extinguished with Pepsi by a Whitney Houston look-alike.

After all the experimentation, 1989 witnessed Young going back to his roots. Freedom, powered by its anthemic single "Rockin' in the Free World," became his most critically lauded album since Rust Never Sleeps, and its follow-up, 1990's Ragged Glory (recorded with Crazy Horse), was similarly celebrated. Since then, Young has been on a streak of critical and commercial success unparalleled by his peers, making music in his third decade even more distinguished than that in his first. His rediscovery of electric guitar feedback juxtaposed the emergence of the American alternative scene, earning him the nickname "The Godfather of Grunge." Young cemented that description with his satisfying 1995 collaboration with Pearl Jam, Mirror Ball, for which he scored a Grammy nomination for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance.

An occasional dabbler in movie soundtracks since 1970, Young composed the music to Jim Jarmusch's film Dead Man, and followed the early 1996 release of that soundtrack with Broken Arrow, a new studio effort with Crazy Horse which garnered a Grammy nod for Best Rock Album. The subsequent summer tour was filmed by Jarmusch for a documentary titled Year of the Horse, and a double live album of the same name is scheduled for release in June 1997.

With wife Pegi, Young co-founded the Bridge School for Handicapped Children near San Francisco, and each year holds a star-studded benefit. Their son Ben has cerebral palsy and attended the school. Young has also founded a company that makes devices for the disabled, as well as high-tech toys — one of the company's projects is manufacturing an improved wheelchair that Young helped design. The irascible elder statesman of rock eschews the trappings of fame and lives a rather reclusive life on his Northern California ranch. He declines most interviews, and has said that he will no longer grant them to Rolling Stone, in particular, because of its perfumed ad inserts: "I don't like the way the magazine smells."

A subsequent summer tour, which spawned a double live album titled Year of the Horse, was filmed by Jarmusch for a 1997 documentary of the same name.