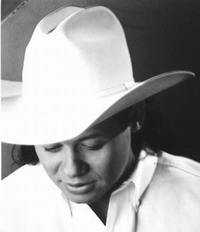

Hubert Neal McGaughey, Jr., the son of Irish and Filipino parents, differed ever so slightly from his schoolmates back in Jacksonville, Texas, and the difference lay somewhere beyond his exotic good looks. When the rodeo would come to town, a summertime highlight, the other kids trailed along in the shadow of the cowboys. Little Neal was elsewhere; he had come to see the entertainers, the country music and television stars headlining the stage show and dance after the rodeo.

Neal McGaughey, Jr. liked every last one of those singers and pickers. He listened hard, and he imagined himself in their boots, and he imitated their licks. Even as a kid he was a singer, a baritone whose gift was nurtured and stretched in gospel quartets and east-Texas choral groups. At home he listened to big-band records, and he danced to disco. His first paying gig came with a rhythm-and-blues band.

Click to Play a clip from "If You Can't Be Good (Be Good at it)" Video Some years later, his own career on the backroads of country music begun, performing in clubs with cute names - his own name changed first to McGoy (the phonetic spelling of his Irish birthright) and finally to McCoy - Neal found himself singing whatever came to mind, as he paid long hard old dues in out-of-the-way places. Country music stars, as everyone knows, are "discovered," and Neal's big day of discovery came in 1981 at a talent show in a Dallas supper club. Six years of touring with Charley Pride later, he recorded his first album. The album went nowhere, slowly.

Problem was, the translation of McCoy in concert to McCoy in the studio was somehow not occurring. All due respect to the producers of Neal's earliest albums, the task may have been impossible. The McCoy stage show is random, erratic, unknown and unknowable in terms of its progression, much less its limits. Working with no set list, Neal's band takes the stage, lays down some chords over which Neal is free to see who's in the audience, say hello, investigate the territory, and set the direction for at least the first two or three tunes.

Then the man begins to demonstrate what those who know him and love him best have long suspected: he has no shame.

He will posture and cock at the first sight of a camera. He will talk to anybody, fan or band member or stagehand, at anytime. He laughs almost as much as he sings. And still the songs arrive, out of nowhere, from rodeo grounds and 1940s ballrooms and southern churches and Ricky Nelson's den as much as from the heart of the classic country experience, with its languid, lovely tales of good love gone bad.

If Neal McCoy in concert is a Texas cyclone equipped with Marshall amps, the new CD, the self-titled Neal McCoy is a baritone in a bottle. But there is no formula here, other than a logical, lyrical progression from the snap and twang, the sheer gorgeousness of the previous two platinum albums. No Doubt About It (1994) with its Billboard Top Ten of the Year status and You Gotta Love That (1995), the signature album that, with Barry Beckett producing again, solidified Neal's sound and established a radio-friendly course for exploration of his vocal style.

No one should be surprised that "Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye" is the first single off the new CD. An unmistakable message saunters through the grand 1960s chestnut, a message that echoes through nine of the ten songs here and indeed through all of Neal's music; love endures; if you let them, the good times will outweigh the bad; the best loves find friendship at their core; simple pleasures matter most.

The album is laced with young-country dance cuts. We can expect to hear "Betcha Can't Do That Again," "That Woman of Mine," and "I Ain't Complainin'," wherever twirls are slow and shuffles are rhythmic. In the lonesome hallways of the lovelorn. "If It Hadn't Been So Good" should win serious consideration as the saddest song of 1996, and the other hymn to good love gone south "Should've Happened That Way," ought to come in second.

On Neal McCoy the baritone is, as always, understand and subtle, effortless in its evocations of everyday stuff. A husband falls for his wife again, and vice versa. An old friend telephones for no particular reason. Some guy finds himself listening to mushy love songs. It's raining, and the roof leaks, but right now this good woman, this nice man are having themselves a dance.

This time round, Neal's voice has found counterpoint. On the road, the band is tight, intuitive, and fun-loving - musical accomplices to the mayhem of the live stage show. In the studio for Neal McCoy the band and the baritone flirt and soar, dip and sway like the two best dancers in the country. This album stacks guitars against Neal's signature vocal phrasings, and the results sound like a cowboy choir. Voice, lead, steel - they all came together in the last chorus of "Going, Going, Gone" as the guitars lead Neal into a glissando wherein "gone" becomes a word of four syllables.

Neal McCoy arrives with an intermission of sorts, a live version of two off-center favorites from the live shows, "Day-0, The Banana Boat Song" and a country-rap version of "The Theme from The Beverly Hillbillies." It's absurd, but it works.

No Neal McCoy album ends in anything but affirmation. The guitars are pumping for "She Can," and we've come full circle. "That Woman of Mine" is here again, and "she can make me smile when I want to cry. When my world gets crazy and I just can't cope, she throws her arms around me and gives me hope."

Sounds like Neal McCoy, all right, up there with his long arms spread, inviting an audience into a tribal hug, some eclectic bit of musical history churning in the background. In that smoky spotlight, as on this new CD, he seems for all the world like nothing so much as a happy little kid with a bull angel's voice way, way into a midsummer's rodeo night.