"Falling out of love is a dangerous thing/With its slippery slopes and its weighted wings/With its birds of prey circling overhead/Casting vulture shadows on barren beds."

She whispers over a trudge of bass drum and brushes on snare, a moan of low harmonica and slither of slide guitar .

"Falling out of love is a treacherous thing/With its crucible kiss and its ravaged ring/With its holy whispers and labyrinth lies/Sacrilegious hungry sighs." If there were no story to tell about this remarkable artist, if there were nothing but the music that haunts every track on Mercy Now, that alone would make the case for Mary Gauthier as one of the most challenging artists to rise up from the underground in a long, long time.

These past few years, people have started catching on, from grad students clustered into Boston cafes to crowds cheering before the main stages at Newport, Telluride, the Strawberry Music Festival, and in venues beyond our shore. Jon Pareles of the New York Times picked her album Filth & Fire as the top indie release of 2002. Rolling Stone acclaimed her "American Gothic tales . delving into physical abuse, drug addiction, abject poverty, and homelessness." CMJ lauded her "piercing honesty" and "powerful singing — her voice cracks more out of weariness than frailty."

But there is a story here, strange and scary, as compelling as the music. Gauthier's path has wound through devastation and despair. She has beaten back demons, lived off the streets, sunk to the bottom of life, turned 18 behind bars, emerged from darkness, and to completely confuse things won notice as a respected restaurateur — all before writing her first song.

It can take a lifetime to write even one line like those that thread through Mercy Now. For Gauthier, that life began in a kind of prison, in which conformity was the lock in the door and each house was as much a cell as any box of steel and stone.

"I was adopted when I was about a year old. My adopted parents tried, but their marriage was doomed. They ended up like zombies. Music saved my life."

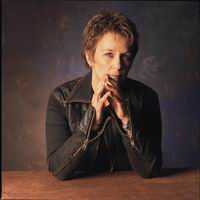

Mary Gauthier — say it: Go-shay — is in Nashville now, at one of the coffee bars where she and her fellow songwriters meet to check in on each other. She's wiry and tough, her speaking voice a little cracked, her laughter quick and easy. When she talks, she looks you right in the eye and doesn't let go.

"It was the only thing I could relate to back in Baton Rouge [Louisiana]. I looked around me and I couldn't relate to my family. I couldn't relate to the neighborhood. I couldn't relate to the people I went to school with hardly at all. I felt like an alien. But I found songs that spoke to me."

But Bob Dylan, John Prine, Jim Morrison, Patti Smith, Neil Young and the others who caught her ear couldn't save her. Maybe their songs made her even more restless, for they were "truth tellers," as she sees it, and truth only put the lies in a brighter light.

At fifteen she stole her parents' car. "I had no idea where I was going," she remembers. "I just knew that if I stayed my life would be in danger — not that somebody was going to kill me, but I felt like I was dying. My father was an alcoholic. My mother cried all the time. She was suicidal. Her mother had cancer. There was chaos and pandemonium in the family."

The years that followed remain a blur. "I went into detox, ended up in a halfway house, got thrown out, lived with my mother again for a week. I ran away again, ended up at another detox and another halfway house, found friends to stay with, and I was off and running for a good ten years. I drove a car through a carwash in the middle of Salina, Kansas, a 17-year-old kid from Baton Rouge. I stole something out of a car — a bottle of pills or something — and I ended up in jail for my 18th birthday. They let me out, I got thrown out of Kansas, and I just kept running."

Years would pass before Mary would find her muse. "I was incapable of writing when I was getting high and drinking," she says. "Most writers can't do it sober; I couldn't do it drunk. Ironically, though, I was capable of going to school and running a business; I just couldn't put words together than meant anything to me."

So, with assistance from the state of Louisiana and from the owner of a restaurant where she had found a waitress gig near the campus, Mary enrolled at LSU as a philosophy major. Her five years there helped her prepare for when she would begin writing. "The most important thing I got from philosophy was that there are no answers," she says. "There are only good questions. There's freedom in knowing that you don't have to know it all, which is why to me, a song should end with a question, not an answer."

When drugs became too hard to handle, Mary dropped out in her senior year, tried and failed to get on top of the situation, and left Baton Rouge for Boston, where she endured several crappy jobs before working the counter at a little café. Somehow she moved ahead in the midst of her addictions; after being promoted to manager, she rounded up some backers who paid her way to the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts, from which she emerged with a plan to open a Cajun restaurant in the Back Bay.

Dixie Kitchen proved a success. "For me, the best part of the gig was the creative part — writing the menu, rewriting the menu, figuring out how the place would look. I used to wake up at night, having come up with a brand new soup in my sleep. But the maintenance was drudgery. Maybe that was a flashback to my parents' monotonous life in the cookie-cutter neighborhood with the cookie-cutter car and the cookie-cutter kids. Whatever it was, I hated it."

So once more Mary ran away — but now she knew where she was going. She tried again to get off the bottle and the drugs, and this time it worked. "There's no way to get sober painlessly," she affirms. "It's like you're going 110 miles an hour down the Autobahn outside of Nuremberg and you slam on the brakes. Everything you've been running from your whole life comes slamming into your ass. It keeps coming for years. And you never have to stop dealing with it."

Then a little miracle happened: Without warning, Mary found herself, for the first time, writing songs. "It was like, bam, two neurons touched, fused, connected, and the next thing you know I'm obsessed with getting words down in a song to make sense of all this, to try and understand my own life."

And so Mary Gauthier wrote her first song, when she was finally clean and sober. She was 35 years old.

The early ones were, by her admission, derivative. But because her mission was to find truth through writing, the next ones came out sharper, less mannered, more painful and redemptive. "I hit my stride when I wrote this song called 'Goddamn HIV,'" she says. "It's written from the perspective of a gay man who's got the virus. That's when I realized that something has to happen when I write — a physiological reaction. If it raises the hair on my arms and puts goose bumps there, I know I've nailed it."

Soon Mary picked up a guitar and headed out to the local coffeehouses, where she waited her turn alongside kids a decade or more younger for her turn in the spotlight. "I was terrified," she admits. "My first night at an open mike, my hands were shaking. My mouth was dry. I forgot the chords. I forgot the words. I was banging into the microphone. I had no idea what I was doing. But I got through it, and I knew I was going to come back and tackle it again . and again and again and again."

No one was more surprised than Mary when her first CD, Dixie Kitchen (1997), earned her a Boston Music Award nomination for "best new contemporary folk artist" — a coup for any first-time performer in the city's hyper-competitive market. "That gave me some confidence. I really started writing hard and strong. I spent less and less time at the restaurant, more and more time at my writing desk. I began coming to Nashville to do workshops with the Nashville Songwriters Association. I was passionate about songs, the way I once was about soup," she laughs.

Eventually she sold her share in Dixie Kitchen to finance her second album, Drag Queens in Limousines (1999). With that, she smiles, "all hell broke loose": Rolling Stone gave it a four-star rave, MOJO, Q, Gavin Report, and other publications joined in on the chorus, and she reaped an Independent Music Award, "country artist of the year" honors from GLAMA, and multiple dates throughout the folk festival circuit and Europe. The third release, Filth & Fire (2002), inspired critics in the Freeform American Roots poll to pick her as the top female artist of the year, and won benediction from No Depression as "the best singer/songwriter album of the year."

On Mercy Now Mary reaches even higher by dredging deeper through the backwaters of her life. These songs reflect her mastery of image, her determination to find precisely the right word, sometimes through months of labor over a single line or idea, and her ability to bring it all to life through her gifts as a performer. As on her previous efforts, there is plenty of darkness on Mercy Now, spread over the wreckage of love on "Falling Out of Love," enveloping the macabre mourners that parade through "Wheel Inside the Wheel," and raging through the storms of "It Ain't the Wind" ("When the wild winds let up, when the violence wanes, you'll think of me then, when you're watching it rain.")

There are different shadows, more mournful than threatening, in "Empty Spaces," "Rhymer," and "Drop in the Bucket," each an elegy for lost love. And there is light, in the careful instrumentations — the cello, the violin, the banjo, the Hammond organ, each meticulously placed by Mary and her producer Gurf Murlix — and especially in the lyric to "Mercy Now," a prayer for those Mary once fought and fled.

Mercy, then, takes its place alongside the furies that first whipped Mary's poetry toward its desolate eloquence. Mercy Now is the first of her albums to arrange the circle of emotions into a mirror of our lives as well as hers. For all that she has accomplished, personally and artistically, this is the step that will elevate Mary Gauthier into the company of the very greatest of writers and singers — the truth tellers, if you will.

"What is the difference between a truth teller and a great songwriter?" she muses. "I think it comes from writing about the struggle. Instead of running from the pain, a truth teller runs head on into it. Somewhere along the way I figured out that the most intimate part of me is the most universal part of me. I've figured out that the artist's job is to reveal that universal human experience. There's got to be a way to go inside and pull out the bigger truth and use it as a mirror in which other people can see themselves."

Of course, there is. Without it, there's no explanation for Mercy Now, for these songs and stories that can change your life.

"Every living thing could use a little mercy now . I love life and life itself could use some mercy now." — Mary Gauthier