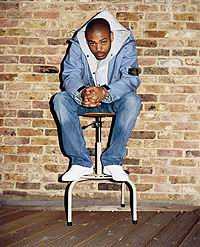

Meet 19-year-old Kane ‘Kano’ Robinson: garage’s lyricist laureate, the MC’s MC, the street poet who knows it, a pirate frequency all of his own amid the scramble of the national garage airspace. A key member in East London’s reigning N.A.S.T.Y. Crew, he has talent, credibility and vision coming out of his pores, and let’s not even mention his looks – handsome enough to melt knicker elastic at a thousand paces, he’s currently out of love, and weighing out the options: ‘Single… yeah,’ Kano grins. ‘I’m happy about that. There’s girls, but I seen people go through a lot of stress with relationships. There’s nothing wrong with having a girlfriend, but… there’s time for that.’

And there’s time for a lot more, beginning with headline billing as Most Requested spitter on garage’s underground circuit – for further details, just check the posters adorning any traffic lights near you. With not one but two alternative careers – he trialled as centre-forward for Chelsea and Norwich as a schoolkid, and then cruised through graphic design courses on the back of nine GCSES to win a place at Greenwich University, which he then spurned – music’s gain is very much academia and sport’s loss. He is native and resident of East Ham in far-East London, where garage is less a sounds than a way of life. And today Kano is ready to roll out his new single ‘Typical Me’ and forthcoming debut album alongside a whole new mode of expression that threatens to leave the competition looking decidedly one-dimensional.

In the magnificently unblemished flesh, Kano is affable, assured, unhurried, unafraid. He smiles at girls as they walk past, but holds his tongue. For someone who’s making career out of hyperspeed chat, he’s surprisingly quiet. Where others front, Kano reflects. His timing is nanosecond perfect. As a schoolkid he didn’t approach garage with the blind zeal of the evangelist. Get this - he ‘eased into it.’

‘It was a mess-about really,’ he says. ‘Most of my friends in the playground would be battling each other. My brother got decks when he was 16, then I started in writing lyrics and making tapes in my bedroom, and started making beats on my computer, and then made a couple of songs.’

Neither did he have to look too far from his ends to find the music the best expressed how he felt about the world he was growing into. Kano’s radio buzzed with the sounds of East London pirate. There were no pictures of Tupac or Biggie on his walls. Instead his tastes bypassed the US and alighted directly on Jamaica, where the roots of both his own family and garage’s embryonic new school lie.

‘I used to just listen to what was going on round here’, he explains. ‘My family is Jamaican, so I was also into Bounty Killer, Shabba and Buju Banton. I saw Elephant Man and Vibes Kartel in Jamaica. You can learn off them, the way they perform: the crowd just have to get into it. They give you a performance. They’re entertainers.’

The quiet ambition Kano nurtured between his bedroom walls paid off almost instantly. At 16, when he was still looking up to D Double E, the one-man garage industry who heads up eastside contenders N.A.S.T.Y Crew, he delivered ‘Boys Love Girls’ - a treatise on the politics of the sexual playground expressed in the language the playground best understands. As Dizzee’s ‘I Luv U’ and Wiley’s chilly ‘Igloo’ and ‘Ice Rink’ single were standardising UK garage’s next genetic strain, the wavering melody lines and panic-button riddim of ‘Boys Love Girls’ gained a steady footing on the underground.

‘I was 16 when I did Boys Love Girls,’ Kano reflects. ‘When I made that I wasn’t even into it properly. I just made it and didn’t know what it was gonna do. It introduced me into this whole thing. And that’s how people heard me first. It’s my signature – I still spit that lyric at raves.’

Additionally, he still reflects a lot, a personal characteristic that defines Kano’s lyrical themes and vocal style. Far more than a mere hype man for whichever DJ is rocking the rave or torching the local pirate station with 20 of his mates, Kano’s agenda edges garage towards a far more ambitious level of articulacy. It’s been said that he comes over as the quiet kid… ‘…But I’m just thinking,’ he notes. ‘I’m thoughtful. I’m quiet more than I speak. I got a lot of tunes with inside thoughts. It’s thinking about what I’m getting into, if it’s too late to turn back, if this is really what I want to do. That’s the kind of person I am.’

That too illustrates the wider shift in the way garage and grime is incrementally developing from disposable dance floor music into a far deeper and infinitely more subtle medium capable of expressing the turbulent inner life of Britain’s excluded urban underclass – a demographic discovering their own identity and voice through microphones, cheap computer technology and the sawn-off idiom of pirate music. ‘The new skool thing isn’t really about dancing, whereas with garage everyone dances to it,’ Kano says. ‘The MCs were just hyping up the crowd, but now the MCs have got a lot to say. Basically spitting verses about what’s going on rather than just hyping the crowd. There are tunes to make you dance, but it’s more about listening to the MCs.

A case in point is ‘How We Livin’, where Kano observes “I got this long intro and I got nothing to say…” - before filling the next three and half minutes with the kind of insight last heard on Grandmaster Flash’s The Message’ and polemic you’d more closely associate with Question Time than Cosa Nostra of a bank holiday Saturday. It’s perhaps fitting that Kano’s now spending less time battling for airtime on the pirates – he started on Flavour FM with Demon, before moving to Déjà Vu – and more time in the studio, honing his debut into what could be an outstanding chapter in British black music. What’s abundantly clear in Kano’s scheme that his strain of garage has now - literally - outgrown its roots.

‘A lot of station don’t really play grime no more,’ he says. ‘And it's understandable. They play like old skool and R&B, but with loads of MCs in the studio it gets a bit mad. Too many people in the studios, fights and all that.’

Time is on his side, yet time is also paradoxically short, meaning there isn’t a spare moment for a tedious debate on the lingering ‘what-do-you-call-it theme. ‘I can’t be bothered to put a name on it,’ he declares. ‘The Neptunes don’t sound like Kanye West who doesn’t sounds like Dre - but it’s all hip hop. That’s why I just say garage. Grime is cool, but I don’t call it grime.’

At Mike Skinner’s personal request Kano has been busy working with The Mitchell Brothers, a pair of East London MCs championed and produced by The Streets. Along with D Double E and Lethal B, Kano recently detonated an evening of East London style over in Berlin. ‘No one knew us over there but we got them hyped cos we were enjoying it ourselves. That’s the key – to enjoy it yourself. If I was at a rave and saw people on stage not really having a good time, not giving it their all, I wouldn’t I give it my all.’

Kano’s game plan is clear – he’s enjoying himself, and it’s a safe bet a spin of ‘Ps & Qs’ or new ‘Typical Me’ will mean you will too. It may be a long way off, but if The Streets-style fame comes knocking on his door, Kano’s tactics would be true to his rectitude.

‘Fame would piss me off, I reckon,’ he concludes. ‘I bet Mike wishes he could sell as many records but not be so famous. Your face is just blatant and everyone knows who you are. It must be a nightmare… I’d probably stay indoors a lot. Some people get into this for the fame. I don’t. I just want to do it for the music.’