John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist, who advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to end all slavery. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas and made his name in the unsuccessful raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

President Abraham Lincoln said he was a "misguided fanatic" and Brown has been called "the most controversial of all 19th-century Americans."[1] Brown's actions are often referred to as "patriotic treason", depicting both sides of the argument.

John Brown's attempt in 1859 to start a liberation movement among enslaved African Americans in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) electrified the nation. He was tried for treason against the state of Virginia, the murder of five proslavery Southerners, and inciting a slave insurrection and was subsequently hanged. Southerners alleged that his rebellion was the tip of the abolitionist iceberg and represented the wishes of the Republican Party. Historians agree that the Harpers Ferry raid in 1859 escalated tensions that, a year later, led to secession and the American Civil War.

Brown first gained attention when he led small groups of volunteers during the Bleeding Kansas crisis. Unlike most other Northerners, who advocated peaceful resistance to the pro-slavery faction, Brown demanded violent action in response to Southern aggression. Dissatisfied with the pacifism encouraged by the organized abolitionist movement, he reportedly said "These men are all talk. What we need is action—action!" [2] During the Kansas campaign he and his supporters killed five pro-slavery southerners in what became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre in May 1856, in response to the raid of the "free soil" city of Lawrence. In 1859 he led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (in modern-day West Virginia). During the raid, he seized the armory; seven people were killed, and ten or more were injured. He intended to arm slaves with weapons from the arsenal, but the attack failed. Within 36 hours, Brown's men had fled or been killed or captured by local farmers, militiamen, and U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee. Brown's subsequent capture by federal forces, his trial for treason by the state of Virginia, and his execution by hanging in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia) were an important part of the origins of the American Civil War, which followed sixteen months later.

When Brown was hanged after his attempt to start a slave rebellion in 1859, church bells rang, minute guns were fired, large memorial meetings took place throughout the North, and famous writers such as Emerson and Thoreau joined many Northerners in praising Brown.[3]

Historians agree John Brown played a major role in starting the Civil War.[4] His role and actions prior to the Civil War as an abolitionist, and the tactics he chose, still make him a controversial figure today. He is sometimes memorialized as a heroic martyr and a visionary and sometimes vilified as a madman and a terrorist. Some writers, such as Bruce Olds, describe him as a monomaniacal zealot, others, such as Stephen B. Oates, regard him as "one of the most perceptive human beings of his generation." David S. Reynolds hails the man who "killed slavery, sparked the civil war, and seeded civil rights" and Richard Owen Boyer emphasizes that Brown was "an American who gave his life that millions of other Americans might be free." For Ken Chowder he is "at certain times, a great man", but also "the father of American terrorism."[5]

Brown's nicknames were Osawatomie Brown, Old Man Brown, Captain Brown and Old Brown of Kansas. His aliases were Nelson Hawkins, Shubel Morgan, and Isaac Smith. Later the song "John Brown's Body" (the original title of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic") became a Union marching song during the Civil War.

In 1938–1940, American painter John Steuart Curry created Tragic Prelude, a mural of John Brown holding a gun and a Bible. In 1941, Jacob Lawrence illustrated the life of John Brown in The Legend of John Brown, a series of twenty-two gouache paintings. By 1977, the original paintings were in such fragile condition they could not be displayed, and the Detroit Institute of Arts commissioned Lawrence to recreate the series as a portfolio of silkscreen prints. The result was a limited edition portfolio of twenty-two hand-screened prints. The works were printed and published with a poem, John Brown, by Robert Hayden, which was commissioned specifically for the project. Though John Brown had been a popular topic for many painters, The Legend of John Brown was the first to explore the topic from an African American perspective.Contents [hide] 1 Early years 2 Homestead in New York 3 Actions in Kansas 3.1 Pottawatomie 3.2 Palmyra and Osawatomie 4 Later years 4.1 Gathering forces 4.2 Raid 4.3 Imprisonment and trial 4.4 Victor Hugo's reaction 5 Death and aftermath 5.1 Senate investigation 5.2 Aftermath of the raid 6 Posthumous view of Brown's character 7 Screen portrayals 8 Notes 9 References 9.1 Secondary sources 9.2 Primary sources 9.3 On-line 9.4 Historical fiction 10 External links

[edit] Early years

John Brown was born May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. He was the fourth of the eight children of Owen Brown (February 16, 1771 – May 8, 1856) and Ruth Mills (January 25, 1772 – December 9, 1808) and grandson of Capt. John Brown (1728–1776).[6]

In 1805, the family moved to Hudson, Ohio, where Owen Brown opened a tannery. Brown's father became a supporter of the Oberlin Institute (original name of Oberlin College) in its early stage, although he was ultimately critical of the school's "Perfectionist" leanings, especially renowned in the preaching and teaching of Charles Finney and Asa Mahan. Brown withdrew his membership from the Congregational church in the 1840s and never officially joined another church, but both he and his father Owen were fairly conventional evangelicals for the period with its focus on the pursuit of personal righteousness. Brown's personal religion is fairly well documented in the papers of the Rev Clarence Gee, a Brown family expert, now held in the Hudson [Ohio] Library and Historical Society.

As a child, Brown lived briefly in Ohio with Jesse R. Grant, father of future general and U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant.[7]

At the age of 16, John Brown left his family and went to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where he enrolled in a preparatory program. Shortly afterward, he transferred to the Morris Academy in Litchfield, Connecticut.[8] He hoped to become a Congregationalist minister, but money ran out and he suffered from eye inflammations, which forced him to give up the academy and return to Ohio. In Hudson, he worked briefly at his father's tannery before opening a successful tannery of his own outside of town with his adopted brother.

In 1820, Brown married Dianthe Lusk. Their first child, John Jr, was born 13 months later. In 1825, Brown and his family moved to New Richmond, Pennsylvania, where he bought 200 acres (81 hectares) of land. He cleared an eighth of it and built a cabin, a barn, and a tannery. Within a year the tannery employed 15 men. Brown also made money raising cattle and surveying. He helped to establish a post office and a school. During this period, Brown operated an interstate business involving cattle and leather production along with a kinsman, Seth Thompson, from eastern Ohio.

In 1831, one of his sons died. Brown fell ill, and his businesses began to suffer, which left him in terrible debt. In the summer of 1832, shortly after the death of a newborn son, his wife Dianthe died. On June 14, 1833, Brown married 16-year-old Mary Ann Day (April 15, 1817—May 1, 1884), originally of Meadville, Pennsylvania. They eventually had 13 children, in addition to the seven children from his previous marriage.

In 1836, Brown moved his family to Franklin Mills, Ohio (now known as Kent). There he borrowed money to buy land in the area, building and operating a tannery along the Cuyahoga River in partnership with Zenas Kent. [5] He suffered great financial losses in the economic crisis of 1839, which struck the western states more severely than had the Panic of 1837. Following the heavy borrowing trends of Ohio, many businessmen like Brown trusted too heavily in credit and state bonds and paid dearly for it. In one episode of property loss, Brown was even jailed when he attempted to retain ownership of a farm by occupying it against the claims of the new owner. Like other determined men of his time and background, he tried many different business efforts in an attempt to get out of debt. Along with tanning hides and cattle trading, he also undertook horse and sheep breeding, the last of which was to become a notable aspect of his pre-public vocation.

In 1837, in response to the murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy, Brown publicly vowed: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!” Brown was declared bankrupt by a federal court on September 28, 1842. In 1843, four of his children died of dysentery. As Louis DeCaro Jr shows in his biographical sketch (2007), from the mid-1840s Brown had built a reputation as an expert in fine sheep and wool, and entered into a partnership with Simon Perkins Jr of Akron, Ohio, whose flocks and farms were managed by Brown and sons. Brown eventually moved into a home with his family across the street from the Perkins' Mansion located on Perkins Hill. Both homes still remain and are owned and operated by the Summit County Historical Society. As Brown's associations grew among sheep farmers of the region, his expertise was often discussed in agricultural journals even as he widened the scope of his travels in conjunction with sheep and wool concerns (which often brought him into contact with other fervent anti-slavery people as well). In 1846, Brown and Perkins set up a wool commission operation in Springfield, Mass., to represent the interests of wool growers against the dominant interests of New England's manufacturers. Brown naively trusted the manufacturers at first, but soon came to realize they were determined to maintain control of price setting and feared the empowerment of the farmers. To make matters worse, the sheep farmers were largely unorganized and unwilling to improve the quality and production of their wools for market. As shown in the Ohio Cultivator, Brown and other wool growers had already complained about this problem as something that hurt U.S. wools abroad. Brown made a last-ditch effort to overcome the manufacturers by seeking an alliance with European-based manufacturers, but was ultimately disappointed to learn that they also wanted to buy American wools cheaply. Brown traveled to England to seek a higher price. The trip was a disaster as he incurred a loss of $40,000 (over $980,000 in today's dollars), of which Col. Perkins bore the lion's share.

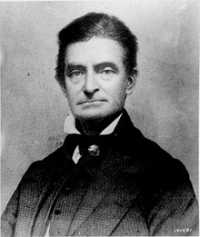

First known photograph of John Brown, c.1846

The Perkins and Brown commission operation closed in 1849; subsequent lawsuits tied up the partners for several more years, though popular narrators have exaggerated the unfortunate demise of the firm with respect to Brown's life and decisions. Perkins absorbed much of the loss, and their partnership continued for several more years, Brown nearly breaking even by 1854. The men remained friends after ending their partnership amicably. Brown was a man of great talent and judgment in farming and sheep raising, but he was not a business administrator. The Perkins and Brown years not only reveal Brown as a man with a widely appreciated specialization (long since forgotten), but reflect his perennial zeal for the underdog which drove him to struggle on behalf of the economically vulnerable farmers of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and western Virginia a decade before his guerrilla activities in Kansas. His attitude evolved with the advent of the Underground railroad. He also helped publicize David Walker's speech called Appeal.[9] [edit] Homestead in New York

John Brown's Farm, North Elba, New York

In 1848, Brown heard of Gerrit Smith's Adirondack land grants to poor black men, and decided to move his family among the new settlers. He bought land near North Elba, New York (near Lake Placid), for $1 an acre, although he spent little time there. After he was executed, his wife took his body there for burial. Since 1895, the farm has been owned by New York state.[10] The John Brown Farm and Gravesite is now a National Historic Landmark. [edit] Actions in Kansas

In 1855, Brown learned from his adult sons in the Kansas territory that their families were completely unprepared to face attack, and that pro-slavery forces there were militant. Determined to protect his family and oppose the advances of pro-slavery supporters, Brown left for Kansas, enlisting a son-in-law and making several stops just to collect funds and weapons. As reported by the New York Tribune, Brown stopped en route to participate in an anti-slavery convention that took place in June 1855 in Albany, New York. Despite the controversy that ensued on the convention floor regarding the support of violent efforts on behalf of the free state cause, several individuals provided Brown some solicited financial support. As he went westward, however, Brown found more militant support in his home state of Ohio, particularly in the strongly anti-slavery Western Reserve section where he had been reared. [edit] Pottawatomie Main article: Pottawatomie Massacre

John Steuart Curry, Tragic Prelude, (1938–40), John Brown and the clash of forces in Bleeding Kansas

Brown and the free state settlers were optimistic that they could bring Kansas into the union as a slavery-free state. But in late 1855 and early 1856 it was increasingly clear to Brown that pro-slavery forces were willing to violate the rule of law in order to force Kansas to become a slave state. Brown believed that terrorism, fraud, and eventually deadly attacks became the obvious agenda of the pro-slavery supporters, then known as "Border Ruffians." After the winter snows thawed in 1856, the pro-slavery activists began a campaign to seize Kansas on their own terms. Brown was particularly affected by the Sacking of Lawrence in May 1856, in which a sheriff-led posse destroyed newspaper offices and a hotel. Only one man, a Border Ruffian, was killed. Preston Brooks's caning of anti-slavery Senator Charles Sumner also fueled Brown's anger. These violent acts were accompanied by celebrations in the pro-slavery press, with writers such as Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow of the Squatter Sovereign proclaiming that pro-slavery forces "are determined to repel this Northern invasion, and make Kansas a Slave State; though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims, and the carcasses of the Abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed disease and sickness, we will not be deterred from our purpose" (quoted in Reynolds, p. 162). Brown was outraged by both the violence of the pro-slavery forces, and also by what he saw as a weak and cowardly response by the antislavery partisans and the Free State settlers, who he described as "cowards, or worse" (Reynolds pp. 163–164).

Biographer Louis A. DeCaro Jr. further shows that Brown's beloved father, Owen, had died on May 8, 1856 and correspondence indicates that John Brown and his family received word of his death around the same time. The emotional darkness of the hour was intensified by the real concerns that Brown had for the welfare of his sons and the free state settlers in their vicinity, especially since the sacking of Lawrence seems to have signaled an all-out campaign of violence by pro-slavery forces. Brown conducted surveillance on encamped "ruffians" in his vicinity and learned that his family was marked for attack, and furthermore was given reliable information as to pro-slavery neighbors who had aligned and supported these forces. The pro-slavery men did not necessarily own any slaves, although the Doyles (three of the victims) were slave hunters prior to settling in Kansas. According to Salmon Brown, when the Doyles were seized, Mahala Doyle acknowledged that her husband's "devilment" had brought down this attack to their doorstep – further signifying that the Browns' attack was probably grounded in real concern for their own survival.

Sometime after 10:00 pm May 24, 1856, it is suspected they took five pro-slavery settlers – James Doyle, William Doyle, Drury Doyle, Allen Wilkinson, and William Sherman – from their cabins on Pottawatomie Creek and hacked them to death with broadswords. Brown later claimed he did not participate in the killings, however he did say he approved of them. [edit] Palmyra and Osawatomie

A force of Missourians, led by Captain Henry Pate, captured John Jr. and Jason, and destroyed the Brown family homestead, and later participated in the Sack of Lawrence. On June 2, John Brown, nine of his followers, and twenty local men successfully defended a Free State settlement at Palmyra, Kansas against an attack by Pate. (See Battle of Black Jack.) Pate and twenty-two of his men were taken prisoner (Reynolds pp. 180–181, 186). After capture, they were taken to Brown's camp, and received all the food that Brown could find. Brown forced Pate to sign a treaty, exchanging the freedom of Pate and his men for the promised release of Brown's two captured sons. Brown released Pate to Colonel Edwin Sumner, but was furious to discover that the release of his sons was delayed until September.

In August, a company of over three hundred Missourians under the command of Major General John W. Reid crossed into Kansas and headed towards Osawatomie, Kansas, intending to destroy the Free State settlements there, and then march on Topeka and Lawrence.[11]

Statue of John Brown in Osawatomie, Kansas

On the morning of August 30, 1856, they shot and killed Brown's son Frederick and his neighbor David Garrison on the outskirts of Pottawatomie. Brown, outnumbered more than seven to one, arranged his 38 men behind natural defenses along the road. Firing from cover, they managed to kill at least 20 of Reid's men and wounded 40 more.[12] Reid regrouped, ordering his men to dismount and charge into the woods. Brown's small group scattered and fled across the Marais des Cygnes River. One of Brown's men was killed during the retreat and four were captured. While Brown and his surviving men hid in the woods nearby, the Missourians plundered and burned Osawatomie. Despite being defeated, Brown's bravery and military shrewdness in the face of overwhelming odds brought him national attention and made him a hero to many Northern abolitionists,[13] who gave him the nickname "Osawatomie Brown". This incident was dramatized in the play Osawatomie Brown.

On September 7, Brown entered Lawrence to meet with Free State leaders and help fortify against a feared assault. At least 2,700 pro-slavery Missourians were once again invading Kansas. On September 14 they skirmished near Lawrence. Brown prepared for battle, but serious violence was averted when the new governor of Kansas, John W. Geary, ordered the warring parties to disarm and disband, and offered clemency to former fighters on both sides.[14] Brown, taking advantage of the fragile peace, left Kansas with three of his sons to raise money from supporters in the north. [edit] Later years [edit] Gathering forces

By November 1856, Brown had returned to the East, and spent the next two years traveling New England raising funds. Amos Adams Lawrence, a prominent Boston merchant, contributed a large amount of capital. Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, secretary for the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, introduced Brown to several influential abolitionists in the Boston area in January 1857. They included William Lloyd Garrison, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker and George Luther Stearns, and Samuel Gridley Howe. A group of six wealthy abolitionists – Sanborn, Higginson, Parker, Stearns, Howe, and Gerrit Smith – agreed to offer Brown financial support for his antislavery activities; they would eventually provide most of the financial backing for the raid on Harpers Ferry, and would come to be known as the Secret Six[15] and the Committee of Six. Brown often requested help from them with "no questions asked" and it remains unclear of how much of Brown's scheme the Secret Six were aware.

On January 7, 1858, the Massachusetts Committee pledged to 200 Sharps Rifles and ammunition, which was being stored at Tabor, Iowa. In March, Brown contracted Charles Blair of Collinsville, Connecticut for 1,000 pikes.

John Brown in 1859

In the following months, Brown continued to raise funds, visiting Worcester, Springfield, New Haven, Syracuse and Boston. In Boston he met Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He received many pledges but little cash. In March, while in New York City, he was introduced to Hugh Forbes, an English mercenary, who had experience as a military tactician gained while fighting with Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy in 1848. Brown hired him to be the drillmaster for his men and to write their tactical handbook. They agreed to meet in Tabor that summer.

Using the alias Nelson Hawkins, Brown traveled through the Northeast and then went to visit his family in Hudson, Ohio. On August 7, he arrived in Tabor. Forbes arrived two days later. Over several weeks, the two men put together a "Well-Matured Plan" for fighting slavery in the South. The men quarreled over many of the details. In November, their troops left for Kansas. Forbes had not received his salary and was still feuding with Brown, so he returned to the East instead of venturing into Kansas. He would soon threaten to expose the plot to the government.

William Maxson house, Springdale, Iowa, Brown's headquarters in 1857-1858.

Because the October elections saw a free-state victory, Kansas was quiet. Brown made his men return to Iowa, where he fed them tidbits of his Virginia scheme. In January 1858, Brown left his men in Springdale, Iowa, and set off to visit Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. There he discussed his plans with Douglass, and reconsidered Forbes' criticisms. Brown wrote a Provisional Constitution that would create a government for a new state in the region of his invasion. Brown then traveled to Peterboro, New York and Boston to discuss matters with the Secret Six. In letters to them, he indicated that, along with recruits, he would go into the South equipped with weapons to do "Kansas work".

Brown and twelve of his followers, including his son Owen, traveled to Chatham, Ontario where he convened on May 8 a Constitutional Convention. The convention was put together with the help of Dr. Martin Delany. One-third of Chatham's 6,000 residents were fugitive slaves, and it was here that Brown was introduced to Harriet Tubman. The convention assembled 34 blacks and 12 whites to adopt Brown's Provisional Constitution. According to Delany, during the convention, Brown illuminated his plans to make Kansas rather than Canada the end of the Underground Railroad. This would be the Subterranean Pass Way. He never mentioned or hinted at the idea of Harpers Ferry. But Delany's reflections are not entirely trustworthy. Brown was no longer looking toward Kansas and was entirely focused on Virginia. Other testimony from the Chatham meeting suggests Brown did speak of going South. Brown had long used the terminology of the Subterranean Pass Way from the late 1840s, so it is possible that Delany conflated Brown's statements over the years. Regardless, Brown was elected commander-in-chief and he named John Henrie Kagi as Secretary of War. Richard Realf was named Secretary of State. Elder Monroe, a black minister, was to act as president until another was chosen. A.M. Chapman was the acting vice president; Delany, the corresponding secretary. In 1859, "A Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America" was written.

Although nearly all of the delegates signed the Constitution, very few delegates volunteered to join Brown's forces, although it will never be clear how many Canadian expatriates actually intended to join Brown because of a subsequent "security leak" that threw off plans for the raid, creating a hiatus in which Brown lost contact with many of the Canadian leaders. This crisis occurred when Hugh Forbes, Brown's mercenary, tried to expose the plans to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and others. The Secret Six feared their names would be made public. Howe and Higginson wanted no delays in Brown's progress, while Parker, Stearns, Smith and Sanborn insisted on postponement. Stearn and Smith were the major sources of funds, and their words carried more weight.

To throw Forbes off the trail and to invalidate his assertions, Brown returned to Kansas in June, and he remained in that vicinity for six months. There he joined forces with James Montgomery, who was leading raids into Missouri. On December 20, Brown led his own raid, in which he liberated eleven slaves, took captive two white men, and stole horses and wagons. On January 20, 1859, he embarked on a lengthy journey to take the eleven liberated slaves to Detroit and then on a ferry to Canada. While passing through Chicago, Brown met with Allan Pinkerton who arranged and raised the fare for the passage to Detroit.[16]

Over the course of the next few months he traveled again through Ohio, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts to draw up more support for the cause. On May 9, he delivered a lecture in Concord, Massachusetts. In attendance were Bronson Alcott, Rockwell Hoar, Emerson and Thoreau. Brown also reconnoitered with the Secret Six. In June he paid his last visit to his family in North Elba, before he departed for Harpers Ferry. He stayed one night enroute in Hagerstown, Maryland at the Washington House, on West Washington Street. On June 30, 1859 the hotel had at least 25 guests, including I. Smith and Sons, Oliver Smith and Owen Smith and Jeremiah Anderson, all from New York. From papers found in the Kennedy Farmhouse after the raid, it is known that Brown wrote to Kagi that he would sign into a hotel as I. Smith and Sons.[17] [edit] Raid Main article: John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

Harper's Weekly illustration of U.S. Marines attacking John Brown's "Fort"

Brown arrived in Harpers Ferry on July 3, 1859. A few days later, under the name Isaac Smith, he rented a farmhouse in nearby Maryland. He awaited the arrival of his recruits. They never materialized in the numbers he expected. In late August he met with Douglass in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he revealed the Harpers Ferry plan. Douglass expressed severe reservations, rebuffing Brown's pleas to join the mission. Douglass had actually known about Brown's plans from early in 1859 and had made a number of efforts to discourage blacks from enlisting.

In late September, the 950 pikes arrived from Charles Blair. Kagi's draft plan called for a brigade of 4,500 men, but Brown had only 21 men (16 white and 5 black: three free blacks, one freed slave, and a fugitive slave). They ranged in age from 21 to 49. Twelve of them had been with Brown in Kansas raids.

On October 16, 1859, Brown (leaving three men behind as a rear guard) led 18 men in an attack on the Harpers Ferry Armory. He had received 200 Beecher's Bibles -- breechloading .52 caliber Sharps rifles -- and pikes from northern abolitionist societies in preparation for the raid. The armory was a large complex of buildings that contained 100,000 muskets and rifles, which Brown planned to seize and use to arm local slaves. They would then head south, drawing off more and more slaves from plantations, and fighting only in self-defense. As Frederick Douglass and Brown's family testified, his strategy was essentially to deplete Virginia of its slaves, causing the institution to collapse in one county after another, until the movement spread into the South, essentially wreaking havoc on the economic viability of the pro-slavery states. Thus, while violence was essential to self-defense and advancement of the movement, Brown's hope was to limit and minimize bloodshed, not ignite a slave insurrection as many have charged. From the Southern point of view, of course, any effort to arm the enslaved was perceived as a definitive threat.

Initially, the raid went well, and they met no resistance entering the town. They cut the telegraph wires and easily captured the armory, which was being defended by a single watchman. They next rounded up hostages from nearby farms, including Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington. They also spread the news to the local slaves that their liberation was at hand. Things started to go wrong when an eastbound Baltimore & Ohio train approached the town. The train's baggage master tried to warn the passengers. Brown's men yelled for him to halt and then opened fire. The baggage master, Hayward Shepherd, became the first casualty of John Brown's war against slavery. Ironically, Shepherd was a free black man. Two of the hostages' slaves also died in the raid.[18] For some reason, after the shooting of Shepherd, Brown allowed the train to continue on its way.

A. J. Phelps, the Through Express passenger train conductor, sent a telegram to W. P. Smith, Master of Transportation of the B. & O. R. R., Baltimore:

Monocacy, 7.05 A. M., October 17, 1859. Express train bound east, under my charge, was stopped this morning at Harper's Ferry by armed abolitionists. They have possession of the bridge and the arms and armory of the United States. Myself and Baggage Master have been fired at, and Hayward, the colored porter, is wounded very severely, being shot through the body, the ball entering the body below the left shoulder blade and coming out under the left side. [19]

News of the raid reached Baltimore early that morning and then on to Washington by late morning.

In the meantime, local farmers, shopkeepers, and militia pinned down the raiders in the armory by firing from the heights behind the town. Some of the local men were shot by Brown's men. At noon, a company of militia seized the bridge, blocking the only escape route. Brown then moved his prisoners and remaining raiders into the engine house, a small brick building at the entrance to the armory. He had the doors and windows barred and loopholes were cut through the brick walls. The surrounding forces barraged the engine house, and the men inside fired back with occasional fury. Brown sent his son Watson and another supporter out under a white flag, but the angry crowd shot them. Intermittent shooting then broke out, and Brown's son Oliver was wounded. His son begged his father to kill him and end his suffering, but Brown said "If you must die, die like a man." A few minutes later he was dead. The exchanges lasted throughout the day.

Illustration of the interior of the Fort immediately before the door is broken down

Barclay Coppock[20]

Edwin Coppock

By the morning of October 18 the engine house, later known as John Brown's Fort, was surrounded by a company of U.S. Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee of the United States Army. A young Army lieutenant, J.E.B. Stuart, approached under a white flag and told the raiders that their lives would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused, saying, "No, I prefer to die here." Stuart then gave a signal. The Marines used sledge hammers and a make-shift battering-ram to break down the engine room door. Lieutenant Israel Greene cornered Brown and struck him several times, wounding his head. In three minutes Brown and the survivors were captives. Altogether Brown's men killed four people, and wounded nine. Ten of Brown's men were killed (including his sons Watson and Oliver). Five of Brown's men escaped (including his son Owen), and seven were captured along with Brown. Among the killed raiders were John Henry Kagi; Lewis Sheridan Leary and Dangerfield Newby; those hanged besides Brown were John Anthony Copeland,

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown_(abolitionist)