“Since I was 12 years old, my plan was to play professional golf. I was determined that golf was going to be my life. I couldn’t wait to get out there and start playing with Tiger Woods and the guys on tour, said Jake Owen, who’d mapped out his life at 12 years old.

Jake Owen’s aim was true; unfortunately, one summer afternoon he suffered a career ending injury. That accident turned out to be a blessing in disguise. When he put down his golf clubs, he picked up a guitar, and a new plan emerged; one that would take him off the fairway and onto Music Row, bypassing—he admits--- many of the traditional steps along the route.

Jake Owen was born 15 minutes after his fraternal twin Jarrod, but he caught up quickly. Raised in Vero Beach, Florida, the two took advantage of the year-round warm weather to indulge in all kinds of sports---tee-ball, baseball, football.

When he was 12 years old, he narrowed down the field, and took up golf, initially because it allowed him to hang out with his father. “I decided to start playing golf because I wanted to do something with my dad. Once I started playing, I found out that I was pretty good.” So good in fact, that soon his closest friends were the middle-aged men that he played weekend tournaments with. He remembers the first time that he won a club tournament; the prize was a trophy and a personalized parking spot, something at 15 that he had little use for. “Those guys were pretty ticked off,” he admits with a grin.

After high school graduation, he and his brother drove to Tallahassee, where Jarrod would play tennis, and he would be a walk-on member of the golf team, for Florida State University. A waterskiing accident altered his course. “I had to have reconstructive surgery. I was so depressed. I didn’t have a Plan B.” Over the next several months, his life plans also underwent some radical reconstruction.

“My brother was going to practice, going to classes, doing all the things I should have been doing. I was sitting in the apartment getting more and more down. As it turned out, my neighbor had a guitar, so I asked if I could borrow it. To pass the time I just started teaching myself to play. I had always loved music. I grew up listening to classic country, Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard. My dad loved Vern Gosdin and Keith Whitley. So I kept going to class and started getting totally into playing guitar and teaching myself these songs.”

One afternoon he walked into a campus bar, Pot Belly’s, drawn by the live music. “There was a guy in there, just him, playing guitar and singing. I thought to myself, ‘I can do that.’” The following day, undeterred by the fact this his entire public entertainment experience consisted of singing Boot Scootin’ Boogie for his fifth grade graduation, Owen went back to the bar, found the owner, and asked what he needed to do to get a playing gig. Apparently, proximity and availability won him the job and he was on stage that very night. “I just plugged in my acoustic guitar and started singing.” He made $75 a night, free beer, and caught the eyes of a few ladies. “The whole time I was golfing, I never had a girl come up to me and say, ‘Wow, nice clubs.’ Or, ‘I love your swing.’ But a guitar is a whole different story.”

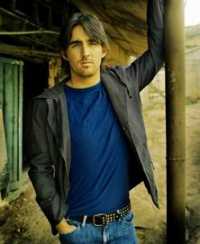

The voice that emerged from some previously untapped internal spring was mighty impressive too. The rich, resonant baritone that colored the songs of artists decades older than him belied his youth, lent credibility to his relative lack of experience, and provided some gravitas to his model-worthy good looks.

“At first, it was me and a guitar on a stool in front of 100 people; then it was 400 people. So I started a band called Yee Haw Junction, which was the real name of a town I knew. As much as he loved the traditional country artists, performing covers of their material began to wear on Owen. “I felt like I couldn’t find my own voice singing covers and the only way I could feel some honesty in what I was doing was to write my own songs. The first two I did were It’s Been A While and 8 Second Ride. I got compliments on them, enough that I felt like maybe I had something.”

With nine hours of school remaining to get his degree, he found himself at a turning point, and turned to his parents for advice. “I called home, and when my mom answered, I told her I needed to talk to them, and asked her to get my dad on the phone too. I told them that I had really been working hard at my music, and that I felt like after my injury, a door had opened for me to another way, one that didn’t really involve English or Political Science, which were my majors. My dad had always wanted to be a professional golfer, and he could have been, but life and responsibilities prevented him from pursuing that dream. He told me that if this was my dream, and if it were my gift, them I should go for it, and that I had their blessing.”

Two days later, Owen packed his clothes, some furnishings, his two guitars and a notebook full of songs into his Forerunner and headed north. “I didn’t know anyone in Nashville, but I knew I needed to go to the place where it happens. I found an apartment in Bellevue, about 10 miles from town. That first week, I basically stayed in my apartment writing songs.”

When he finally made his first visit to Music Row, it wasn’t to a record label, or a publisher, or a management office. It was to open a bank account, a deposit that ultimately reaped immeasurable interest and dividends.

“When Becky (the bank employee) asked me what I did for a living, I told her I was a singer/songwriter. She said she would like to hear my music sometime; luckily, I just happened to have a CD,” he says with a laugh. The following day, he got a phone call from Warner-Chappell Music, expressing interest in his material. Though that arrangement did not ultimately work out, Owen felt that his decision to pursue a career in Nashville has been validated. A chance meeting over lunch with producer Jimmy Ritchey (Clay Walker, Mark Chesnutt) confirmed it. “We just hit it off right away,” he says. “We became friends first. But he was very supportive. For the next 18 months, we basically hung out, writing songs. I hardly even went out of my apartment. I wrote a song with Jimmy and Chuck Jones called Ghost that we thought Kenny Chesney was going to record. He didn’t, but that sort of put me on the RCA radar. Jimmy got me together with Renee Bell, Senior Vice President for SonyBMG Nashville and she signed me.”

Less than two years after moving to Nashville, the 24-year-old former golfer had a recording deal and basically brought a finished album to the table.

Owen had already earned the respect of an artist whose opinion he held in high regard. “Soon after I signed to RCA, we flew to Chicago to see Kenny Chesney. We went on his bus after the show and when Renee introduced us, she says, ‘Jake is the guy who co-wrote Ghost.’ He starts singing it back to me, word for word! I couldn’t believe it. He told me he loved the song, and wanted to record it, but it just didn’t work out. It blew my mind. Two years ago, I was that kid in the nosebleed section of the Leon County Civic Center in Tallahassee, watching him run back and forth on stage, a million miles away. I wondered what that would feel like. And there I was, sitting on his bus, one foot away from him, listening to him sing my song back at me.”

Ghost did make it on to Startin’ With Me, Owen’s debut album, which---as the young artist points out—is entirely composed of songs he wrote or co-wrote.

“When I look at my life, where I am right now, I know how improbable it is. I am totally aware of that. I haven’t been doing it and dreaming about it since I was five years old, it doesn’t run in my family, I didn’t grow up singing in church, I didn’t spend 10 years in honky-tonks. But I have always worked hard at whatever I have done, whether it was golf or writing songs or playing at Potbelly’s in Tallahassee. I feel like things happen for a reason, and we are each here for a reason. Maybe the accident that ended my golfing career happened because I was supposed to do this. How many people would my golf game have affected? I hope that my music and my songs can touch people, like I have been touched by other artists’ songs. Is that something that you measure by years or dues? I think it’s something from the heart, and who can measure that?”