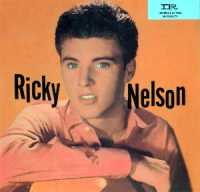

Rick Nelson was one of the very biggest of the '50s teen idols, so it took awhile for him to attain the same level of critical respectability as other early rock greats. Yet now the consensus is that he made some of the finest pop/rock recordings of his era. Sure, he had more promotional push than any other rock musician of the '50s; no, he wasn't the greatest singer; and yes, Elvis, Gene Vincent, Carl Perkins, and others rocked harder. But Nelson was extraordinarily consistent during the first five years of his recording career, crafting pleasant pop-rockabilly hybrids with ace session players and projecting an archetype of the sensitive, reticent young adult with his accomplished vocals. He also played a somewhat underestimated role in rock & roll's absorption into mainstream America — how bad could rock be if it was featured on one of America's favorite family situation comedies on a weekly basis?

Nelson entered professional entertainment before his tenth birthday, when he appeared with father Ozzie (once a jazz musician), mother Harriet, and brother David on a radio comedy series based around the family. By the early '50s, the series was on television, and Ricky grew into a teenager in public. He was just the right age to have his life turned around by rock & roll in 1956 and started his recording career almost accidentally the following year. The story's sometimes been told that he had no professional singing ambitions until he recorded his debut single to impress a girlfriend. The single, a cover of Fats Domino's "I'm Walkin'" that went to number four, was helped immensely (as all of his early singles would be) by plugs on the Ozzie & Harriet TV show.

So far the script was adhering to the Pat Boone teen idol prototype — a whitewash of an R&B hit stealing the thunder from the pop audience, sung by a young, good-looking fella with barely any musical experience to speak of. What happened next was easy to predict commercially but surprisingly satisfying musically as well. Nelson was a fairly hip kid who preferred the rockabilly of Carl Perkins and Elvis Presley to the fodder dished out for teen idols, and over the next five years he would offer his own brand of rockabilly music, albeit one with some smooth Hollywood production touches and occasional pure pop ballads. Nelson recruited one of the greatest early rock guitarists, James Burton, to supply authentic licks (another great guitarist, Joe Maphis, played on some early sides). Some of his best and toughest songs ("Believe What You Say," "It's Late") were written by Johnny and/or Dorsey Burnette, who had previously been in one of the best rockabilly combos, the Johnny Burnette Rock 'n Roll Trio. Ricky could rock pretty hard when he wanted to, as on "Be-Bop Baby" and "Stood Up," though in a polished fashion that wasn't quite as wild and threatening as rockabilly's Southern originators.

Nelson really hit his stride, though, with mid-tempo numbers and ballads that provided a more secure niche for his calm vocals and narrow range. From 1957 to 1962, he was about the highest-selling singer in the U.S. except for Elvis, making the Top 40 about 30 times. "Poor Little Fool" and "Lonesome Town" (1958) were early indications of his ballad style; in the early '60s, "Travelin' Man," "Young World," "Teen Age Idol," and other hits pointed to a more countrified, mature style as he honed in on his 21st birthday (by which time he would shorten his billing from "Ricky" to "Rick"). He could still play rockabilly from time to time, the most memorable example being "Hello, Mary Lou" (co-written by Gene Pitney), with its electrifying James Burton solos.

Nelson was lured away from the Imperial label by a mammoth 20-year contract with Decca in 1963 (which would be terminated prematurely in the mid-'70s), and for a year or so the hits continued, at a less frenetic pace. Early-1964's "For You," however, would be his last big smash of the '60s. The fault wasn't all the Beatles and changing music trends — on both singles and albums, much of the material was either substandard pop or dusty Tin Pan Alley standards, although isolated tracks still generated some sparks. He wasn't exactly starving, as he continued to appear on Ozzie and Harriet. But by the mid-'60s even that institution was declining in popularity, leading to its cancellation in 1966.

Nelson had a strong country feel to much of his material from the beginning, and by the late '60s it was becoming dominant. He covered straight country material by the likes of Willie Nelson and Doug Kershaw and formed one of the earliest country-rock groups, the Stone Canyon Band, with musicians who had played (or would play) with Poco, Buck Owens, Little Feat, and Roger McGuinn. A cover of Bob Dylan's "She Belongs to Me" made the Top 40 in 1970, but his country-rock outings attracted more critical acclaim than commercial success, until 1972's "Garden Party." A rare self-composed number, based around the frosty reception granted his contemporary material at a rock & roll oldies show, it became his last Top Ten hit.

Nelson would continue to record off and on for the next dozen years and toured constantly, yet he was unable to capitalize on his assets. A big part of the problem was that although Nelson wanted to play contemporary music, he didn't write much of his own material, which was a basic precept of self-respecting rock acts after the advent of the Beatles. Nor did he tap into good outside compositions, and there's little of interest on the albums he recorded over the last decade or so of his life. He died (along with his fiancée) in a private plane crash on December 31, 1985, on his way to a New Year's Eve gig in Dallas, at the age of 45.