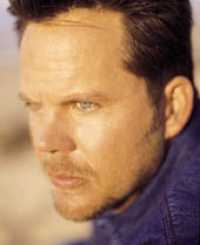

Those are words Gary Allan has heard whispered before. Debuting when he did in 1996, at a time when Nashville was scratching a rash of suburban cowboy hat-wearing newcomers, it was perhaps an inevitable response. But he had the edge of experience. Having honed an individual style on the honky-tonk circuit in his native California since age 12, Allan is nothing if not resilient, and like the long line of honky-tonk icons whose music has inspired him - Lefty Frizzell, Merle Haggard, Johnny Horton, Waylon Jennings, George Jones, Willie Nelson, Buck Owens - he's learned that the best way to meet a challenge is head-on. With a smile.

"There were these guys at Buck's place last night," Allan says, the day after giving a by-invitation performance at a Bakersfield birthday celebration for Buck Owens. "I was signing their Gretsch guitars. They were way into punk, and they said, 'Man, we thought you were just another hat act out of Nashville, and you rawk!' When people see you're real, they're so impressed, and they so want something like that. I've had those guys at my shows since I was 15. Our shows are different that way - I don't worry about politics too much. I go in and I have fun."

If Allan sounds relaxed, he's earned the right. After playing countless smoky bars with his dad as a teen, he led his own band through the clubs and fairs of Southern California for several years before signing with Decca Records and releasing two albums that each generated Top 10 hits (single "It Would Be You" climbed to #5). His just-completed third album, Smoke Rings In The Dark, is by far his most honest and rewarding release to-date. And the hard-working entertainer achieved that feat following the most tumultuous year the music industry's seen in decades. When Decca closed in January, corporate maneuvers could have relegated Allan to the "Whatever Happened To...?" column in tabloid rags. Instead, he was one of only four artists picked up by parent company MCA. His new deal afforded him the time and resources to create a more mature, career-defining record.

Co-produced by top MCA honchos Mark Wright and Tony Brown (a "magic combo" who had never produced together before, and specifically requested by Allan), Smoke Rings In The Dark features a more muscular sound, replete with some swing, bluesy shuffle and twang. Allan even tackles Del Shannon's "Runaway," a staple of every working band's song list. Country sounds come courtesy of Western country sidemen like pedal steel man Dan Dugmore, Allan's longtime bandmate Jake Kelly, and former Faron Young/George Jones fiddler Hank Singer.

"I always thought Gary had a very distinctive sound," Brown comments. "On Smoke Rings In The Dark, this new creative team (Brown, Wright, Allan) really maxed out a direction - we found Gary's musical identity." Adds Wright, "When I first heard Gary play live, it was all about his vibe and musical presence. On this record, we've finally captured the essence of his live performance."

While Nashville contemporaries issue safe pop garnished with occasional steel licks, Allan has synthesized the hard honky-tonk vibe with the high-energy immediacy of his live shows. But it's on ballads like the sophisticated title tune, Harley Allen's "Bourbon Borderline," and Buddy Brock's classic-sounding "Don't Tell Mama" that he really shows the depth and command of his critically praised "aching tenor."

A great singer sounds like they've climbed inside the song and are living it as they sing; there's no distance between their vocal and the song's emotion. When Allan sings, whether he's parsing a lyric with humor or pain, he sounds like he's down with the dust and sweat and compromise of everyday life. No high-glam stylings here.

Capturing that mix - the light and the dark, the laughter with the anger, the conservative and the unusual - goes to the heart of the sometimes contradictory cultural traditions that helped shape the divorced father of three. Allan calls the region around Orange County, California home, an area rich in country music history. It's one of the few places in Southern California with working cattle ranches, where cowboys still rope and brand and go two-stepping at night.

"We get asked a lot at shows, 'What's a guy from California doin' playin' country music?'" Allan says. "There's a lot happening on the West Coast. And it's different than Nashville. I never heard the terms 'radio-friendly' or 'commercial value' until I got to Nashville. When we were writing songs in California, we wrote 'em for how we thought they would come off in a club-y'know, 'How's this gonna be to sing live to people?'"

A short drive west from those cowboy roundups are the beach communities where Allan loves to surf - and where the punk and modern-rock scene still thrives. Interestingly, many of its pierced and tattooed denizens are also exuberant fans of country legends like Johnny Cash, Buck Owens and Hank Williams. Allan sees them at his own shows, and believes they respond to country music's relevancy.

"It's real life," he says. "The great country songs, they're powerful - I don't care what kind of music you listen to, they have a lot of soul. That's what a lot of country's lacking today."

Soul was a priority for Allan while hunting for songs for the new album. He heeded the lessons he's learned from years of reading audiences. The music - more specifically, the industry - has always gone through cycles. What outlasts trends are true stories and strong songs. Allan credits the new album's quality to the players and the fact that he was allowed to do three full song searches with publishers. Additionally, he hosted his own private guitar pull in a living room with cream-of-the-crop songwriters like Guy Clark, Harlan Howard, Harley Allen, Shawn Camp and Byron Hill. "They were there to pitch me songs, and they all pitched 'em acoustically," Allan says with enthusiasm. "It was awesome." Three of the album's best songs - Camp's "Sorry," and Allen's "Learning to Live With Me" and "Bourbon Borderline" - came from that enjoyable return to tradition.

That intimate setup also completed a circle, in a way, by returning to the basic importance of the singer and the song -- and listening. Allan's record deal was cinched by his extensive performance experience on the club circuit, where, like any stage-savvy veteran, he learned to listen to his audience and what makes them respond. For Allan, it's the live moments connecting him to an audience through song that still define country music.