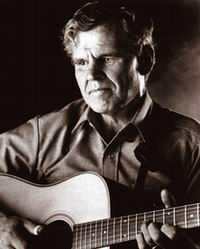

Arthel "Doc" Watson is without doubt a living legend in acoustic music. For more than three decades, Doc Watson has been America's most renowned and influential folk guitar stylist. Now 79 years of age, he's mostly retired but his few selective performances show no signs of his enormous talents being dimmed by either age or fewer concert dates on the road. At any given Doc Watson performance, one will see and hear not only a guitar player of the finest caliber, but also an intelligent, witty, down-to-earth 'man of the mountains' who loves to share the music of his heart and home. Doc is an extraordinary entertainer who never fails to capture the admiration and affection of his audience. His concerts are filled with hot flatpicking tunes, slow romantic ballads, gutsy blues numbers, delicately fingerpicked melodies, and an old time gospel song or two. Each song is sung with unmatched clarity, each tune played with a dexterity that has placed Doc Watson's name in the music history books.

Doc did not set out from his Appalachians mountain home to become a famous musician. In fact, if given his druthers, he never would have struck out on the road to make a living as a performer. While music would have been a part of his life no matter what, carpentry, electrical work, mechanics, or even engineering would have been Watson's calling of choice, if he had been given that choice. Sadly, a childhood eye infection, exacerbated by a congenital vascular disorder near his eyes, took Doc's vision by the time he was one year old. Doc has always referred to his blindness only as a hindrance, not a disability. He would tell you, however, given the opportunity, that one of the very few regrets of his long and productive life is not having been blessed with the ability to see the smiles on the faces of his loved ones.

Arthel Lane "Doc" Watson was born in Stoney Fork Township, near what is now Deep Gap, NC, on March 3, 1923. His father, General Dixon Watson, was a day laborer and a farmer, who actively sung in the Baptist church and played the banjo. His mother, Annie, often would gather the family to sing hymns or read from the Bible. Doc's family was a musically inclined one and as he remembers, "There was the old phonograph around the house, and, of course, I heard the singing at the church, and my mother sang a few of the old ballads when she'd be knitting some of the boys' overalls or cooking or something or other. Never heard Dad, except when he was singing the good old gospel songs - he was singing when I was in church from the time I could remember - up until he made that little old homemade banjo and taught me a few tunes on it."

Doc's first instrument, bought for him by his father, was the harmonica, which he started playing at approximately five years of age. By age 11, his musical talent already growing, he had picked up the banjo, made with the help of his grandmother's cat, which became the instrument's drum. Doc's conscience is clear on that point, however, because as he remembers "I never knew the animal. I never petted it. I never heard it howl or anything that I remember of. It just got old and decrepit and couldn't eat and was blind, and it was miserable. Dad persuaded my brother to put it out of its misery. And he did it without making it suffer."

As a young teenager, while Watson attended the North Carolina State School for the Blind in Raleigh, he learned a few guitar chords from a friend. This accomplishment created the impetus for his father eventually buying Doc his first guitar. As Doc recalls, "My real interest in the music was the old 78 records and the sound of the music, I loved it. And I began to realize that one of the main sounds on those old records I loved was the guitar. One of my brothers had borrowed one from a cousin and I was foolin' with it and he says, Dad just says if you'll learn to play a song on it by the time I get in from work this evening, we'll go in to town and get you one. Well, I knew some chords and I just played the rhythm chords to 'When Roses Bloom in Dixieland'. I had some money saved in my piggy bank, so we took that and he finished it up and got me a $12 Stella, which was a pretty good little guitar at the time." Later in his teenage years, Watson earned enough money sawing wood to buy his own guitar from Sears, Roebuck. He began playing music with his older brother, Linny, in the style of the old-time brother duets, like the Louvins, the Monroe Brothers, the Delmore Brothers and the Carter Family. "I just loved the guitar when it came along. I loved it," Doc recalls. "The banjo was something I really liked, but when the guitar came along, to me that was my first love in music." When Watson was 19, he got a gig performing for a radio show. The announcer felt "Arthel" was too stuffy and was searching for a replacement when someone in the audience shouted "Call him Doc." The name stuck and perseveres to this day.

Not only did Doc Watson come from a musical background, but he married into another family of music when, at the age of 23, he wed his 15-year-old third cousin Rosa Lee Carlton, whose father, Gaither Carlton, was a fiddler with whom Watson played regional hymns and ballads. Doc and Rosa Lee Watson had two children, Eddy Merle, named after guitar great Merle Travis, and in 1951, Nancy Ellen. Throughout the 1950's, Doc supported his family by playing music, tuning pianos, and with great reluctance accepting some financial aid for the blind. He worked primarily in a country dance band, playing an electric Gibson (Les Paul model) guitar with pianist Jack Williams. During this period however, he continued to play the traditional acoustic music of his home with friends Tom "Clarence" Ashley, Clint Howard, and Fred Price, who were all accomplished musicians in their on rights. It was while performing with Ashley, Howard, and Price at Union Grove, North Carolina in 1960 that the now legendary meeting of folklorist Ralph Rinzler and Doc Watson took place. As a legendary folk banjoist, Clarence Ashley introduced Doc to musician and promoter Rinzler, who was impressed by Watson's abilities on the guitar. Rinzler's "discovery" of Watson led to Watson's touring the coffeehouse circuit in the Northeast and eventually took him to the stage of the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, where he was embraced enthusiastically by the folk community, young and old.

On one of this historic festival's stages, a 41-year-old blind guitar player from the North Carolina mountains sat down and began to play. He had wavy, dark hair, a gentle laugh, and a rich, warm baritone that enveloped his audience like a grandfather's hug. He sang songs about lost lives and lost loves, murders and muskrats, shady groves and blackberry blossoms, bringing the sounds of Appalachia to the North. The performance catapulted Doc Watson to the forefront of the folk revival where he has remained ever since. That appearance and a historic concert with the father of bluegrass, Bill Monroe, at Town Hall in New York City in 1964 paved the way for Watson's first recording contract. These events put Watson before the public in a big way at the height of the folk revival, gaining him almost instant renown. As Doc recalls, "I suspect if it hadn't been for Ralph's encouragement I wouldn't be on the musical scene as a professional. Ralph helped me very much. He traveled with me a lot in the early days and taught me a whole lot about how to program sets from the stage until you got to where it's automatic, you don't even have to think about it. He encouraged me an awful lot."

The year 1964 marked another momentous event in Doc Watson's rich life. Upon returning home from a concert tour, Doc found that his son Merle had taken up the guitar. Doc's wife, Rosa Lee, had taught Merle his first chords, and Merle, as Doc now remembers, "just took it and went with it." Doc had entered a period of prodigious musical accomplishment. Merle started recording and touring with him in late 1964 at the Berkeley Folk Festival, and for the next two decades they became opposite sides of the same coin: Doc, the front man, warming the crowd, doing all the vocals; Merle, quiet and bearded, letting his guitar sing harmony for him. Together they made 20 albums and won four Grammys including 'Then and Now" in 1973, and 'Two Days in November' in 1974, but perhaps the enormity of their musical influence on both the acoustic music genre and its fans can best be expressed by one devotee's remembrance of a now long past, but still vivid performance:

"The first time I saw Doc Watson perform, I was standing on a steep bank of dusty red clay. It was a night concert, and I was dog-tired from having pushed a wheelbarrow at work all day. But my older brother had insisted that I go with him and my grandfather to see the blind man with the funny name. That was in the summer of 1972, and I was totally unprepared for what I was about to hear. I was sure that this man being led out onto the stage by the arm of his son would be so uninspired that I could quickly retire to the open benches at the very back of the park, and maybe stretch out and catch a nap. Instead, from the first note struck until the last encore performed, I fought for my position on the bank, unwilling to give any ground to the growing number of longhairs who had suddenly appeared from nowhere, glassy-eyed and swaying, doing awkward little jigs to themselves. To my surprise, the grim-faced man on stage manipulated a guitar in ways his electrified counterparts had never imagined possible. It was an Epiphany, a revelation of sorts, seeing this unassuming man and his son, dressed in white short-sleeved shirts and dark slacks, standing and playing unamplified instruments into two simple microphones. He stood on his feet in the same spot for the whole show and rained music down on the crowd as naturally as he might have plowed a field. The songs he played were traditional, a mixture of bluegrass and folk tales, touched with Jimmie Rodgers blues, cowboy yodels, and classic gospel. As far as I have ever been able to tell, the music he played was America, the south, and Appalachia all woven together with fluid, never-miss-a-lick strokes. I was dumbfounded, where did he come from? Where had he been? More important, where had I been? I was also intimidated, promising myself that upon my return home in the evening, I would chop my pitiful Sears guitar into little pieces and spread it out like shavings in Pop's chicken house. Who was I kidding? Compared to the music made by the unseeing minstrel from North Carolina, I was too embarrassed to even tell anyone that I owned a guitar, much less pretended to play it."

In spite of a surge in the popularity of rock music and a waning of the folk revival in the 1970's, Doc and Merle continued to play to dedicated audiences and win critical acclaim until the dark hours of October 23, 1985 when Doc and Rosa Lee's lives were shattered by Merle's tragic, albeit accidental death. Just days before 'Frets Magazine' honored Merle by naming him the best finger-style guitarist of the year, Eddy Merle Watson rolled his farm tractor on a steep hillside near his home, ending the life of one of the world's great acoustic musicians in a tragedy eerily reminiscent of the blues ballads he loved. The intervening years notwithstanding, the pain still resonates in Doc Watson's voice. "I didn't just lose a good son," he says. "I lost the best friend I'll ever have in this world."

A year after Merle's death, Bill Young, Doc's close friend and picking buddy, Frederick W. "B." Townes, the Dean of Resource Development at Wilkes Community College in Wilkesboro, NC, and Ala Sue Wyke approached him with the idea of doing a benefit concert at the college to raise money for a memorial garden in honor of his deceased son, Merle. Rosa Lee and Doc's daughter, Nancy, suggested they invite a number of Merle's friends to play as well, some of whom were among the country's best acoustic musicians. This dialog germinated the first Merle Watson Memorial Festival in the spring of 1988. Artists played on stage in Wilkes Community College's John A. Walker Center and on the back of two flatbed trucks to a crowd of 4,000 people. This initially modest event, now known as MerleFest, has subsequently become one of the most critically acclaimed acoustic music festivals in the world. MerleFest '95 included over 100 artists and bands, some already legendary and some well on their way, performing on nine stages for nearly 40,000 people, raising funds for the Eddy Merle Watson Garden for the Senses, and providing an economic boost to the Wilkes County economy approaching $1.5 million.

Arthel "Doc" Watson is clearly a folklife and acoustical music icon of legendary proportions who richly deserves his princely place in musical history. He has always been, and still remains, however, one of the most fundamentally modest and self-deprecating men you will ever encounter. When asked how he would like to be remembered by the countless people from all walks of life whom he has enriched with measures of music and wisdom of astonishing clarity, he responded by saying "I would rather be remembered as a likable person than for any phase of my picking. Don't misunderstand me; I really appreciate people's love of what I do with the guitar. That's an achievement as far as I'm concerned, and I'm proud of it. But I'd rather people remember me as a decent human being than as a flashy guitar player. That's the way I feel about it."